This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

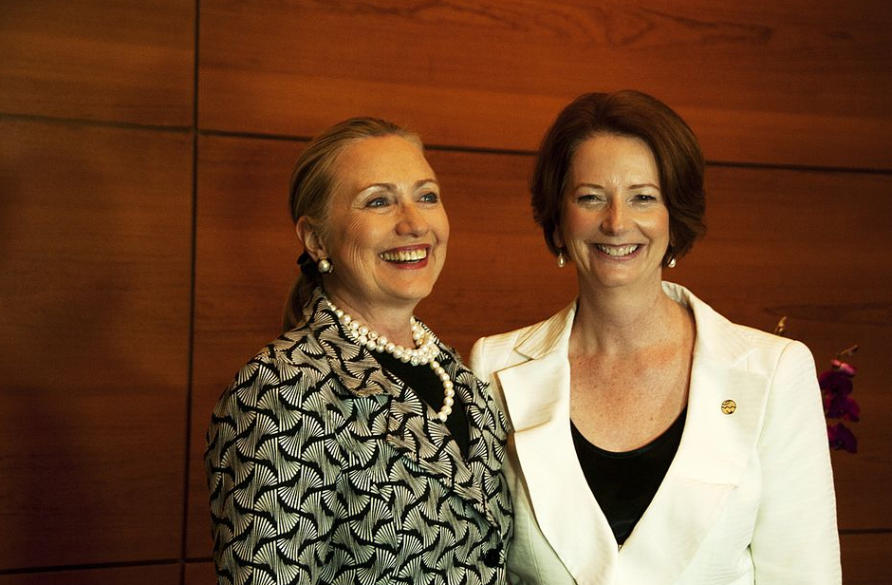

As Julia Gillard read What Happened, the story of her friend Hillary Clinton’s tilt at becoming America’s first female president, she was struck by how many of the anecdotes and observations, when it came to gender, that were almost identical to her own.

Both women were subjected to vicious gender-based smears, from the abuse of shock jocks to placards at demonstrations like “Ditch the Witch” aimed at Ms Gillard, and “Trump that Bitch” for Ms Clinton, and both faced a torrent of online hatred that some described as “almost medieval”.

Both also suffered because of gender stereotyping, and both were challenged by a balancing act that became increasingly difficult the closer they came to the top job.

“If we’re too tough, we’re unlikable. If we’re too soft, we’re not cut out for the big leagues,” Ms Clinton writes. “If we work too hard, we’re neglecting our families. If we put family first, we’re not serious about work. If we have a career but no children, there’s something wrong with us… if we want to compete for higher office, we’re too ambitious.”

These are not the self-serving rationalisations of a candidate who made mistakes that had nothing whatsoever to do with gender. They are the conclusions of researchers like Facebook COO, Sheryl Sandberg, whose key finding is backed by hard data: that the more successful a man, the more people like him, yet the more successful a woman, the more she is disliked.

Finally, both women were periodically challenged on the question of authenticity. As Ms Clinton expressed it: “I’ve been asked over and over again by reporters and sceptical voters, ‘Who are you, really?’”

Sound familiar?

As Ms Gillard said on the issue of gender in her final address as Australia’s first female Prime Minister: “It doesn’t explain everything; it doesn’t explain nothing. It explains something.”

Something else the two women share is an optimism that their experience in politics will make the path for those who follow less difficult, less painful and less sexist.

“What I am absolutely confident of is it will be easier for the next woman and the woman after that and the woman after that, and I’m proud of that,” Ms Gillard declared in that final Prime Ministerial address.

Her fervent hope was that the nation would reflect “in a sophisticated way” about the part gender played in her rise and fall, and factor in the conclusions when the next woman came along.

The same goes for Ms Clinton, who believes her two presidential campaigns have helped pave the way for that country’s first female president; though she is not sure it will be any time soon, saying: “I hope I’ll be around to vote for her – assuming I agree with her agenda.”

Recently, Ms Gillard and Ms Clinton have discussed how they can work together to change perceptions and encourage more women to put themselves forward.

“I’m hopeful there are some things we can do together in the future on these questions of leadership and gender, bringing to that possibility some of our shared experiences,” Ms Gillard says.

“I knew when she was writing the book that she was working through these things and thinking about them very deeply. And one of the things I think she can continue to do, is be a voice for change when it comes to gender and politics.”

Ms Gillard agreed to be interviewed about being the first woman Prime Minister and other aspects of political leadership as she prepares to join John Howard, another former Prime Minister, and others in judging what may well be Australia’s first national award for political leadership, the McKinnon Prize.

Two recipients, an established politician and one with less than five years’ experience, will be announced in March.

Four-and-a-half years after she was torn down by Kevin Rudd before the Labor Party was thrown out of office, Ms Gillard says her conviction about it being easier for the next woman has only strengthened.

“I feel that in Australia and increasingly around the world, that we’re in an era of change for women’s equality and, like all eras of change, it’s not a linear progression of a step forward followed by a step forward followed by a step forward,” she says.

“There are plenty of days where you look at the news media and feel like we’ve gone backwards. But the overall direction of travel is a good one. And I think the fact I served here as the first female (Prime Minister), everybody’s had a bit of time to reflect on the experience now, and I think those reflections would come to the fore the next time we had a woman PM.”

The likely result, she believes, is that there will be far less of an obsessive interest in appearance and in personal life and much less resort to the kind of gender-based use of images that characterised much of the coverage of her prime ministership.

One obvious sign of progress is across the Tasman, where New Zealand’s third female Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, recently announced she will become the first leader of a Western nation in modern times to give birth whilst in office.

This tweet captured the national mood of progress.

Proud to live in a country where the Prime Minister can reconcile starting a family with being in charge. Congrats on the impending arrival @jacindaardern – proud of what you stand for

— Ben Kepes (@benkepes) January 18, 2018

Asked how the perceptions that make it harder for women to rise to leadership positions will change, Ms Gillard says there will only be a shift when the information about bias is known, popularised and understood.

“There’s plenty of research now that people tend to correlate likeability and leadership in men, but tend to think of female leaders as pretty hard-boiled, and must’ve scratched and clawed to get there… and so they’re not very nice.” says Ms Gillard. “That certainly played out hard against Hillary.

“In our world, in our culture, we do have whispering in the back of our brains these sexist stereotypes and one of them is that women leaders aren’t likeable,” she says.

Ms Gillard says one sign that perceptions have changed will come when there is a new female leader, and that leader’s performance is being discussed on one of the political panel shows on TV where journalists interview each other.

“If one of them says, ‘I think a problem for this new leader is she is not viewed as very likeable’, (I hope) that someone else on the panel says, ‘Why do you really think that? Or ‘Is that a bit of unconscious bias at work?’ And then the panel talks it through, when we’ve reached that moment, we will be unpacking all of this in a way that is really healthy.”

The contrast, she adds, is with how the question of likeability played out for Ms Clinton during controversies over her use of her family’s private email server for official communications when she was Secretary of State and Ms Clinton’s response to the 2012 attack on the US diplomatic compound in Benghazi, Libya.

“You imagine a male Secretary of State who had the email problems, had the Benghazi issue, what would people say about him? Well, they might have a variety of views about how competent he is. They might have a variety of views about whether he handled those scandals well or badly,” says Ms Gillard.

“But I doubt people would be saying ‘You know what his trouble is, he’s not very likeable’. I really think that shows us just how gender was at work for Hillary.”

In her memoir, My Story, Ms Gillard implored women and men in all spheres of Australian life to point out sexism when they see it. She now says she is buoyed by the thousands of women sharing their personal stories using the #MeToo hashtag.

“The flashpoint that the internet can provide of bringing people together and empowering the next woman and the next woman to speak up is a truly astonishing thing,” she says.

“I also know that #MeToo needs to end up inclusive of everyone and I think it is overwhelmingly true to say, at the moment, that the power of #MeToo has been at its strongest when allegations of sexual harassment have been in industries where people are famous.

“At the moment, I don’t think #MeToo can say it changed the circumstance for a cleaner who might be a recently arrived migrant, she might not speak much English, and she is being harassed by the head cleaning contractor but she desperately needs that job. I don’t think there’s much about #MeToo that is reaching into her world.”

Ms Gillard began her memoir by recalling how she felt during the walk from her office to deliver her final speech as Prime Minister after being voted out by her Labor colleagues, and how she was determined not to stand before the nation and cry for herself.

“I was not going to let anyone conclude that a woman could not take it,” she wrote. “I was not going to give any bastard the satisfaction. I was going to be resilient one more time.”

So, I ask in a roundabout way, will the next female prime minister feel so compelled to avoid showing any sign of weakness for fear of confirming the sexist stereotype?

“It’s a bit complicated,” Ms Gillard replies. “One of the things I wanted to do was to show that women can thrive, indeed dominate, in adversarial climates and I know that not every feminist is of my view.

“Some feminist writers and thinkers put forward the view that if leadership positions were more equitably shared between men and women, then women would bring a different style to the leadership and it would be a more consensual, more collaborative world.

“I’ve never believed that. I believe that there are some adversarial places in our society for good reasons. Parliament House is one of them. It’s a clash of values.

“But I would hope that we’re in a world where a woman shedding tears because she’s moved by an event doesn’t lead to commentary that says ‘I knew she’d never be tough enough’.”

Ms Gillard was Prime Minister for three years and three days and, for most of that time, she led a minority government. Her formula for getting things done, she says, was exactly the same as when Labor had a majority and when she was a minister.

“You have got to be crystal clear about what it is you have come to do and the big picture policies you want to pursue,” she says. “If you are not crystal clear about what it is you have come to do, you’ll just end up weaving across all issues and never getting profound change done in any of them.”

An example was Ms Gillard’s approach to education. “I wanted to make a real difference for Australian children and I believe we did do that and we have changed the Australian education debate profoundly,” she says.

“Now political parties in Canberra contest as to who has got the best needs-based school funding policy and who is best catering for the disadvantaged. That wasn’t the debate we were having when I started being education minister and took the school funding needs formula through the Parliament as Prime Minister.”

Ms Gillard says she hopes the McKinnon Prize will not only recognise those who display visionary, courageous and collaborative leadership, but will prompt a discussion about what the best political leadership can look like.

She was also drawn to the story of Susan McKinnon, a woman who overcame all manner of adversity and hardship to instil in her two children a sense of social justice, a hunger for knowledge and a commitment to give back when the opportunity arose.

Her son is Melbourne businessman Grant Rule, who set up the Susan McKinnon Foundation in 2015 and committed himself to use the vast majority of the proceeds from his mobile technology business to make a difference for the wider community. The McKinnon Prize is a collaboration between the foundation and the University of Melbourne.

“Her story highlights how access to education can transform people’s lives, and how women, even in the most difficult of circumstances, can create a better situation for themselves and their families – and Susan most assuredly did.”

Michael Gordon is a Melbourne journalist. He won the 2017 Walkley Award for the Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism.

This article was co-published with Fairfax Media.

Read about the Melbourne School of Government’s Pathways to Politics Program for Women here.

Banner: Getty Images