Andrea Carson, Gosia Mikolajczak, Leah Ruppanner & Emily Foley

Originally published in Local Government Studies, NO. AHEAD-OF-PRINT, 1-24, 2023

To cite this article:

Andrea Carson, Gosia Mikolajczak, Leah Ruppanner & Emily Foley (2023) From online trolls to ‘Slut Shaming’: understanding the role of incivility and gender abuse in local government, Local Government Studies, DOI: 10.1080/03003930.2023.2228237

OPEN ACCESS

ABSTRACT

Fair political representation is an important goal of democratic governments, yet Australia lags behind many democracies in women’s representation in elected politics. Attacks against women in public spaces through harassment and verbal abuse have long constrained women’s ease in physical spaces and, in the digital age, this has extended into online spheres. This paper examines the impact of on- and offline incivility on women’s experiences in local politics. It focuses on Australia’s southern state of Victoria and its 79 local government municipalities. We conduct two surveys of men and women elected representatives (N1 = 222, N2 = 205) to determine their experiences during the campaigning period and first year on council. We follow up with in-depth interviews with women who have experienced gender harassment (n = 10) to further understand its impacts. We offer new insights in to a ‘push factor’ that contribute to women leaving elected local government and their political underrepresentation.

© 2023 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

Introduction

Gender parity in legislatures is an important dimension of justice, equality and representative democracy. From a normative perspective, it reflects the women’s right to participate in public life on an equal basis to men, free of direct or indirect discrimination (Sawer 2002: 5050 Vision 2019). It also is critical to women’s descriptive and substantive representation given they constitute about half the population. Countries around the world are looking to identify barriers to women’s equal elected representation. One area of concern is incivility towards elected women in online and offline spaces, yet few studies to date have focused on the nature of incivility directed at women politicians, and even less at the level of local government. This paper addresses this gap using Australia as a case study.

Australia provides an interesting case for understanding factors affecting women’s elected representation, especially given significant improvements in recent elections notwithstanding that gender gaps still exist across all three tiers of government: local, state and federal. The 2022 federal and 2020 local elections in Victoria provided women with historic gains in representation but failed to ameliorate the gender gap. At the federal level, 38.4% of the lower house are women, increasing Australia’s ranking from 57th to 36th in the world. Clearly, this was a major increase, but Australia remains without gender parity and ranks poorly by global standards (IPU 2022). At the local level, Australian women are increasing their overall representation in local government over time, but still lack parity with men. In Victoria, one of Australia’s most populous states, women account for 43.8% of elected local representatives following the 2020 election. Their gains are historic but still parity remains elusive. In response, the Labor Victorian State Government (2016) set the ambitious goal of achieving gender parity in local government by 2025 with associated resources to help achieve this aim. Victorian municipal elections next occur in 2024, this gives women one more election cycle in the four-year local government term to achieve this target and to address obstacles to attracting and retaining women, some of which are identified in this paper.

Australia also provides a powerful and timely case to understand gender equality in politics given the prominent media coverage of gender abuse towards women in politics. The 2021 Australian of the Year, Grace Tame, who helped change state laws relating to communications about under-age sexual assault, used her media profile to shine a spotlight on sexual abuse more broadly. In turn, centre-right federal Liberal party staff member, Brittany Higgins, raised public allegations that she was raped in the federal Parliament House. This revelation led to an outpouring of anger about examples of sexual harassment and abuse of women in Australian politics, in both elected and unelected roles. Subsequently, tens of thousands of women and allies took to the streets to protest gendered violence and inequality in the workplace, in March4Justice rallies across Australia’s major cities (March4Justice n.d.). The federal government ordered an inquiry, known as the Jenkins’ inquiry,1 to understand what changes were needed to make workplaces safer, including parliaments. This watershed moment was critical to raising awareness of the sexual abuse and harassment women face in politics and was a publicised issue during the 2022 federal election campaign.

The salience of this issue proved a considerable liability for the incumbent centre-right Coalition in the 2022 election as they had failed to implement a number of the Jenkins report’s key recommendations.2 As a consequence, the centre-right Liberal party’s weak performance on getting women elected to office came under scrutiny from both within and outside the party as visibility to these issues intensified (Banks 2021). An earlier 2015 internal Liberal party report had warned that unless ‘systemic and attitudinal impediments’ such as ‘chauvinistic behaviour from men’ were addressed, women’s political representation would deteriorate and it would lose women voters, thus jeopardising the party’s future relevance (Duncan and Baird 2021).3 This report proved prescient. At the 2022 federal election, the Coalition fell to 21.4% of women representatives in its lower house, down from the party’s high tide of 25% in 2004. The Coalition lost government to the Australian Labor Party (ALP), with its lowest seat share in the house of representatives’ since 1946. The centre-left ALP won with 46.8% women’s representation in the lower house, achieving its mandatory party quota (i.e., 45% women by 2022, and the only Australian political party with mandatory quotas). These heated national debates about the treatment of women in politics foreground our study into women’s representation at the local government level and the role of incivility and gender abuse in deterring women from entering or staying in politics. Local government is an important, yet understudied area given its role as a pipeline to train women seeking office at state and national levels where women are also underrepresented (Crowder-Meyer and Lauderdale 2014; Holman 2017).

While we acknowledge that decisions to run or not to contest elections are multi-factorial, we focus here on one key obstacle to gender parity in Victorian local government: incivility and gender incivility towards women (relative to men) elected representatives across Victoria’s 79 municipal councils. This neglected area of study is particularly salient given the intensified visibility of these issues in Australia in contemporary times. Incivility and gender incivility found in mainstream and social media are known to play a detrimental role in politics (Pérez-Escolar and Noguera-Vivo 2022). In this article, we examine offline and online incivility and gender incivility during campaigns and elected terms to understand how these transgressions impact women’s decisions to run for local government or, once elected, to recontest. To date, much of the literature on ‘push factors’ that disincentivise women from entering or continuing in politics tends to focus on work-life issues (Carson et al. 2021; Hills 1983). We expand our understanding to include the role of incivility as another ‘push factor’ for women to exit politics. We proceed by briefly examining the international literature on definitions of workplace incivility and canvass the benefits and disadvantages of using social media in political communication, with specific studies on women’s experiences using social media for this purpose. Drawing on this scholarship, and key Australian literature on gender incivility and local government studies, we formulate our research questions followed by an outline of our methods, data and findings. Finally, we conclude with recommendations to help mitigate online and offline gender abuse in politics.

Workplace incivility

Workplace incivility is a type of negative workplace behaviour defined as ‘low-intensity deviant behaviour with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms emphasising mutual respect. Uncivil behaviours are characteristically rude, discourteous, displaying lack of respect for others’ (Andersson and Pearson 1999, 457). Examples of incivility include making derogatory remarks about someone, ignoring them or using a condescending tone when talking to them.

We focus on incivility as a prevalent form of modern discrimination in organisations (Cortina 2008). Incivility is ubiquitous and seemingly innocuous, but nevertheless an insidious form of deviant behaviour. It is more covert and therefore harder to interpret as intentional and to address with relevant policies than other overtly hostile and sexist behaviours. For example, in a study by Cortina et al. (2001), more than 70% of surveyed US public-sector employees reported having experienced some type of workplace incivility in the previous five years. Workplace incivility was frequently associated with psychological distress and thoughts of quitting (see also Schilpzand, De Pater, and Erez 2016 for a review). Importantly, previous studies indicate that women experience higher levels of incivility than men (e.g., Cortina et al. 2013).

Here, we argue that incivility towards women politicians provides a powerful case study given politicians experience incivility from a range or perpetrators beyond the workplace of council staff and other councillors, but also can include the media, the public, and social media users. Thus, the scope and breadth of incivility is broad and may be a central driver for women leaving local politics.

Social media: a new political communication frontier for politicians

Social Media platforms have greatly accelerated the capacity for politicians and the public to directly communicate with one another (Parmelee and Bichard 2011). There are benefits and disadvantages for online political communications. Some argue that technological connectivity provides greater accountability and transparency of democratically elected political representatives (Ceron 2017) and is a powerful tool to widely publicise political platforms and agendas (Kreis 2017). Social media can facilitate both interpersonal and mass communication – or ‘masspersonal communication’ as coined by O’Sullivan and Carr (2018). Yet, mass online communications also offer nascent anonymous spaces for online abuse and harassment between politicians and the public,(Southern and Harmer 2021). Studies find women are more vulnerable to the negative consequences of online trolling and political campaigns. Australian women politicians are no exemption. A Victorian parliamentary inquiry into the role of social media in elections found women politicians disproportionately experienced online gender-based violence (Parliament of Victoria 2021, 154). One cited reason for this gender skew is that women are held to higher standards in their public and personal lives creating a ripe environment for online trolling (Akhtar and Morrison 2019 −325;, pp. 324; Barnes and Beaulieu 2019; Wolbrecht and Campbell 2007). Further, politics is a historically men-dominated communicative space meaning women politicians must navigate complicated gender roles to develop effective or avoidance communication strategies (Celis et al. 2014; Schreiber 2016). Consequently, women’s experiences with online trolling and political campaigns are thought to be a driver for women exiting politics (Ryall 2017). We test this proposition during a critical moment – the 2020 council elections in Victoria – a period during which social media became a critical campaigning tool, in many cases the sole tool, during the COVID-19 pandemic when Victorians were in repeated lockdowns lasting over 250 days in some areas (Vîrtosu 2022). We then follow-up using survey data from councillors about their first year’s experiences in elected office.

International literature on the relationship between women in politics and their use of social media identifies it as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, women use social media more than men to connect with their constituents. Sullivan (2021) showed Canadian women mayors use social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram outside of campaigning periods at a higher rate than men counterparts. The organisation #ShePersisted (Di Meco 2019) apply interview data from women in positions of political power to show social media platforms are useful sites for connectivity with their constituents and accessible avenues to spread their policy agenda, mobilise their constituency and control the political discourse.

On the other hand, Fichman and McClelland (2020) found that tweets by women politicians were trolled more than men politicians when they undertook a content analysis of 3,000 Twitter comments from US Federal politicians. An Inter-Parliamentary Union Issues Brief interviewed 81 female MPs across Council of Europe Member States and found that 58.2% had experienced online abuse across social networks IPU (2018). Similarly, Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan (2019) analysed 2.2 million messages addressed to Canadian politicians and US Senators on Twitter, finding that highly visible women politicians were more heavily targeted by uncivil messages than highly visible men politicians. A Fabian Women report on a UK mentoring and political education programme found that of the 54 mentees4 interviewed, over 75% stated that online abuse and media sexism caused them a ‘fair amount’ or ‘significant’ concern when contemplating political careers (Campbell and Lovenduski 2016). A 2023 US study found a rise in psychological and physical violence against mayors from 2017 to 2021 with younger mayors and women the most likely targets as they threaten the status quo (Herrick and Thomas 2023).

To date, significant research examining the effects of trolling on women politicians derives from Canada (Briggs 2000; Wagner 2020), the UK (Akhtar and Morrison 2019; Gorrell et al. 2020), and the US (Herrick et al. 2021). Gorrell et al. (2020) found that on average, men experienced more incivility (i.e., receiving more general and political abuse) but women received more sexist abuse. Importantly, their 2019 study found a significant number of women UK politicians stated they will not be standing for re-election, citing incivility as a key reason. This presents an important line of inquiry in the Australian context. We know Australian women politicians at the state level receive more online abuse and harassment than men counterparts (Parliament of Victoria 2021). A recent audit of 9,939 local government employees, including councillors, also found about one in four employees (28%) had experienced sexual harassment at work and that it was more prevalent for women (30%) compared to men (25%), particularly for women aged under 35 (VAGO 2020). But little is known of the online experiences of incivility of local councillors.

Gender abuse in Australian politics

Despite a breadth of international literature establishing trends of incivility towards politicians and women, an assessment of online and offline gendered incivility in the Australian context is understudied. There is some research on the online and offline trolling of Australia’s first female Prime Minister, Julia Gillard (Ghazarian and Lee-Koo 2021; Johnson 2015; Morrissey and Yell 2018). However, most studies examine the role of traditional media news outlets in this mistreatment (Walsh 2013, 2021; Williams 2020; Wright and Holland 2014). Gillard’s negative coverage in the press was found to have dire future consequences because it impacted the political aspirations of the next generation of women. Younger women and girls reported that the treatment of Gillard dissuaded them from entering politics as did women’s experiences of abuse across their life courses (Majumdar 2021). Notwithstanding these examples, most Australian inquiries examine incivility and online trolling of high-profile women who are not politicians, such as journalists (Bossio and Holton 2018; Martin 2018), celebrities (Lumsden and Morgan 2017; Weber and Davis 2020) and feminist commentators (Weber and Davis 2020).

A research gap in gendered experiences in Australian local government studies is also apparent. Most research emerged in the 2000’s and first half of the 2010’s and focused largely on factors that influence women’s likelihood of successfully managing a political career such as supportive partners (Briggs 2000) and difficulties such as compartmentalising work from family (Ryan, Pini, and Brown 2005). More recent studies on local government have examined the absence of culturally diverse women and women of colour (Jakimow 2022). Social media is largely absent as a focus of inquiry across these literatures, a significant research void given the acceleration of technology and its increasing importance in contemporary politics. While existing international literature clearly demonstrates that women politicians experience higher rates of online abuse and harassment, it tends to focus at a federal level (Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan 2019).

We fill this void paying careful attention to women representatives’ experiences in online and offline spaces in the context of local government. This is important as local government can serve as a critical training ground for other tiers of government (Briggs 2000, 74; Hills 1983, 40; Weeks and Baldez 2015). Thus, understanding ‘push factors’ that deter women from contesting elections at the local level is critical as having fewer female candidates gaining experience of elections can create a potential chokepoint in the political pipeline for women’s representation to other tiers of elected politics. This hampers the broader goal of achieving gender parity at all levels of representation.

Research questions

This paper explores the extent to which incivility and gender abuse towards women in local government impacts women’s political career trajectories. The literature informs our three research questions, which are:

1.

What form does incivility take in local government?

2.

Is incivility (online and offline) a more common experience for women than for men in local government?

3.

Does incivility and gender abuse affect women’s decisions to seek election to local government?

Answers to these questions are internationally salient and of interest in the Australian context given the commitment to reaching gender parity in local government in Victoria by 2025, combined with national public attention to gender abuse in politics through recent media coverage and the Jenkins’ review.

Method and data

We apply a mixed methods approach using 2020 and 2021 councillor survey and complement it with in-depth interview data with women candidates and councillors aged 45 years and under. These unique data sources enable us to triangulate findings to capture ramifications flowing from the experiences of generalised incivility and gender incivility during an election campaign and in the first year of elected office.

Surveys

Following the local government elections (in October 2020), the entire population of elected Victorian men and women councillors (N = 621: 349 men to 272 women) were invited to participate in an online survey. The survey was open throughout December 2020 and January 2021 and included questions about motivations to run for council, experiences during the election campaign, work-life demands at the start of the new council term, and demographic background. The final sample for analysis included 222 respondents (Mage = 52.70, SD = 13.16) providing a robust sample size of 36% of all elected councillors. The sample was broadly representative of the councillor’s locality (60% respondents from regional councils vs 56% elected; Victorian Electoral Commission, 2020) and with an oversampling of women relative to the electorate (51% of respondents were women vs 44% elected). Of the sample, 12% identified as culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD).

A year later, in December 2021 we invited all councillors to participate in a follow-up survey examining their experiences in the first year of the 2020–2024 council term. The survey included repeat questions from the first survey and additional questions about positive and negative workplace experiences and work-life demands during the first year in council, and intentions to run for council at the end of the four-year term. The final sample for analysis included 205 respondents (Mage = 54.02, SD = 11.60) and was comparable to the 2020 sample (54% women, 40% from regional councils, 10% CALD). We utilise the survey responses from these two waves presented congruently below to identify whether councillor’s experiences extend into their first year in office. All analyses were conducted using R for Windows v. 3.6.3.

Dependent variables

Incivility

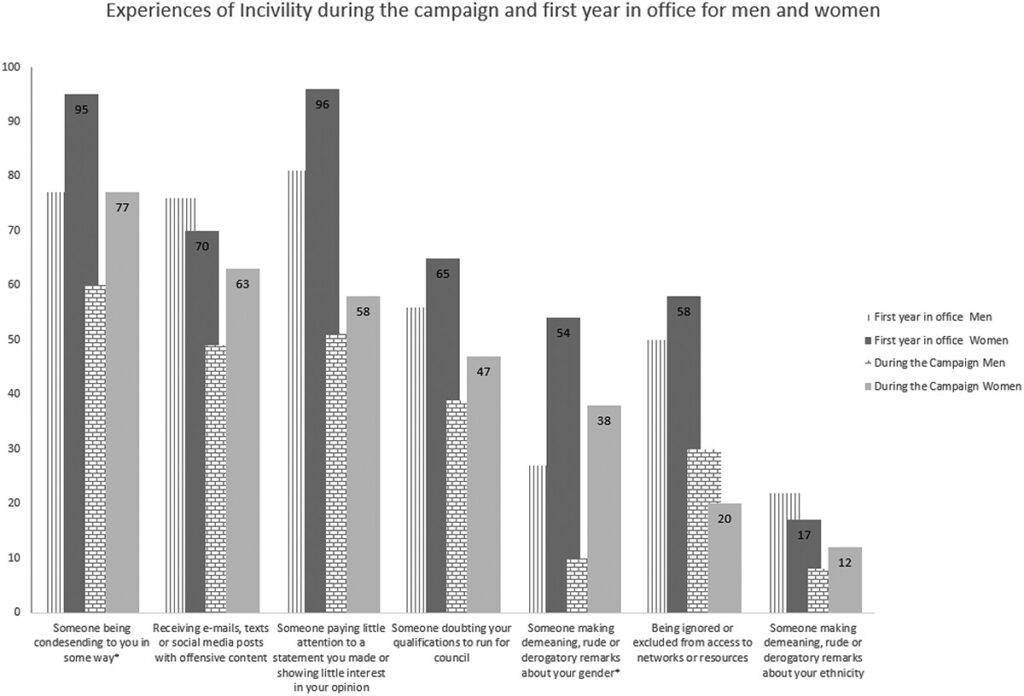

Incivility was measured using selected items (6 items in the 2020 survey and 5 items in the 2021 survey) adapted from the workplace incivility scale (Cortina et al. 2001). Respondents were asked to indicate if they have experienced a range of uncivil behaviours such as someone doubting their qualifications to run for council or being ignored or excluded from access to networks and resources, during: (a) the election campaign with responses ranging from 0-never to 4-multiple times; and (b) in the first year in council with responses ranging from 0-never to 4-very frequently. See for types of incivility that women and men councillors have experienced during the campaign period and in their first year in office. Responses in each survey were highly correlated and thus averaged to create a composite measure of incivility (M = 1.33, SD = 1.09, ω = .91 in the 2020 survey: M = 1.50, SD = 0.91, ω = .86 in the 2021 surveys).

Gender-based incivility

Gender-based incivility was measured with a single item (‘Have you experienced someone making demeaning, rude or derogatory remarks about your gender during the election campaign/in the first year in council’). For this item, we used the same response format as in the remaining incivility items (M = 0.60, SD = 1.17 in the 2020 survey: M = 0.74, SD = 1.03 in the 2021 survey).

Perpetrators of incivility

Respondents who indicated that they have experienced at least one uncivil behaviour during the election campaign/first year in council were then asked to indicate the entities that were most central to their negative experiences (other candidates/incumbent councillors, constituents, media, other; in the 2021 survey we added two categories of perpetrators: council staff and council CEO). We created a series of dummy variables to represent the source of incivility for measurement in the models (1=yes).

Intentions to run in the next election

In the first-year councillors’ experiences survey, we additionally asked respondents whether they considered running for council in the next election (scheduled for 2024). Those who indicated that they would not run were asked a follow-up question about their top three reasons for not considering running again.5 One option included experiences of online and in person abuse (hostility and/or bullying on social media, hostility and/or bullying in person, gender abuse – either online or in person) which we measure dichotomously (1=yes, a top three reason; 0=No, not a top three answer) in our models.

Independent variables

We are interested in how incivility and gender-based incivility is experienced by different groups. Thus, we apply a series of sociodemographic variables to understand these patterns. Our key independent variable is gender (woman = 1; man = 0; respondents who indicated other genders were excluded from analyses due to very low numbers), and given that our expectations from the literature is that women will experience more incivility and gender abuse. We also include measures for age (measured linearly), location (1=regional/rural; 0=urban) and CALD status (1=yes; 0=no). The application of these variables allows us to isolate the impact of gender beyond other dimensions that are shown to contribute to incivility and abuse in politics.

In-depth interviews

After analysing the first tranche of quantitative data that revealed gender abuse was more prevalent for younger women under 45 years of age, we extended our inquiry to this cohort. Through the Victorian Local Governance Association (VLGA) and a women’s Facebook group with 1200 members entitled ‘More Women for Local Government’, we advertised to interview adult women aged 45 and under who had experiences of local government. Purposive sampling was used to achieve a mix of regional/rural and metro-based women. The mean age was 34.4. Ten in-depth interviews were undertaken between February and March 2021. Due to COVID-restrictions the semi-structured interviews occurred online using Zoom and each interview took approximately one hour.6

Results

We begin with an overview of the various forms of incivility that men and women councillors have self-reported during the campaign period and during their first year in office. We combine these two time periods into one graph (see Figure 1) to reveal that both men and women experience various forms of incivility, but for most items women are more likely to encounter these negative experiences than men (as shown with the percentage values attached to women’s experiences in Figure 1). This pattern is consistent with international studies that examined online civility towards politicians (Fichman and McClelland 2020; Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan (2019). Also as expected, the number of councillors who experience forms of incivility is generally higher in the first year than the shorter period of an election campaign.

Notably we see many more women than men experience incivility that ‘remarks upon’ their gender. This particular finding is consistent with the results of Gorrell et al. (2020) study in the United Kingdom that found on average men encountered more general and political abuse, but women received more sexist abuse. We now look in detail at the two surveys and test for statistical differences in experiences of incivility and gender-based incivility for men and women.

Election campaign and first year in office: incivility and gender-based incivility

During the election, men and women councillor’s experienced similar levels of incivility (M = 1.19 for men, M = 1.49 for women, t = −1.90, p = .059) but during the first year in office, women report more incivility (M = 1.64) than men (M = 1.31, t = −2.44, p = .015).

We also find that younger councillors report more incivility during the election (r = −.40, p < .01) and in their first year in office (r = −.29, p < .01) than older councillors. This finding extends also to those who live in metro councils (M = 1.77 during election, M = 1.77 in the first year in office), relative to those from regional/rural councils (M = 1.06 during election, t = 4.57, p < .001; M = 1.33, t = 3.21, p = .002 in the first year in council). During the election period, we find no significant association between generalised incivility and councillor’s CALD status (p = .959), but during the first year in office, CALD councillors report more generalised incivility (M = 2.01) than those who do not identify as CALD (M = 1.44, t = −2.41, p = .025).

When we specify gender-based incivility, we find women report more gender-based incivility than men (M = 0.97 vs M = 0.21, t = 4.78, p < .001) during the election period and into the first year in office (M = 0.99 for women, M = 0.44 for men, t = −3.77, p < .001). We also find younger councillors report more gender-based incivility during the election period (r = −.24, p < .01) and into their first year in office (r = −.24, p < .01). Those in metropolitan areas report no different experience of gender-based incivility during the election period (p = .093) but do report greater experiences during the first year of office (M = 0.94 vs M = 0.61, t = 2.17, p = 0.32). The bivariate statistics indicate that generalised incivility is equally felt by men and women councillors during the election period, but that women councillors experience greater incivility in their first year in office.

Moreover, and a key finding of this study, is that women councillors experience more gender-based incivility than men across the election campaign and during their first year in office. Thus, women councillors are carrying the heavier burden of greater overall and gender-based incivility over their entire experience contesting an election and representing constituents.

To further understand how gender structures experiences of incivility, we ran linear regression models controlling for councillor’s age, CALD status and locality (see Table 1). We find gender has no association with generalised incivility during the election (model 1) and into the first year of office (model 2), meaning that men and women councillors report similar levels of generalised incivility.

Table 1. Linear Regression Results Predicting Incivility during the Election Campaign and First Year in Office.

| Generalised Incivility | Gender-Based Incivility | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election Period | First Year of Office | Election Period | First Year of Office | |

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| (Intercept) | 3.01** | 2.30** | 1.16** | 1.27** |

| Gender | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.68** | 0.49** |

| Age | −0.03** | −0.02* | −0.02* | −0.01* |

| Location | −0.48** | −0.02* | −0.07 | −0.12 |

| CALD | 0.02 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.46 |

| R-Square | .20** | 0.14*** | 0.14*** | 0.13*** |

| N= | 183 | 181 | 183 | 181 |

*p < .05. **p < .01, ***p<.001; gender: woman = 1, man = 0; location: regional/rural = 1, metro = 0; CALD = 1, non-CALD = 0.

We find younger councillors report more generalised incivility during the election campaign (model 1) and into their first year (model 2). Those in metro areas report more generalised incivility during the election (model 1) but not into the first year in office (model 2).

Models 3 and 4 present the results for gender-based incivility. Consistent with expectations and our bivariate statistics above, councillor’s gender had a positive association with gender-based incivility during the election (model 3) and into the first year in office (model 4) uniquely explaining eight per cent and four per cent of variance in gender-based incivility, respectively. While the magnitude is not large, it is meaningful as it indicates a specific problem that needs to be addressed.

When we assess these relationships for different groups of women during the election, we find a significant interaction between councillor’s gender and CALD status, see Table 2 below.

Table 2. Linear Regression Results Predicting Incivility with Gender and CALD status.

| Generalised Incivility | Gender-Based Incivility | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election Period | First Year of Office | Election Period | First Year of Office | |

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| (Intercept) | 3.08** | 2.30*** | 1.29*** | 1.27** |

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.56 | 0.45 |

| Age | −0.03** | −0.02* | −0.02** | −0.01* |

| Location | −0.50** | −0.25 | −0.09 | −0.12 |

| CALD | −0.32 | 0.57 | −0.38 | 0.28 |

| Gender X CALD | 0.63 | −0.30 | 1.12* | 0.33 |

| R-Square | .21** | 0.14** | 0.16** | 0.14** |

| N= | 183 | 181 | 183 | 181 |

*p < .05. **p < .01, ***p<.001; gender: woman = 1, man = 0; location: regional/rural = 1, metro = 0; CALD = 1, non-CALD = 0.

Simple slope analysis using Johnson-Neyman significance intervals indicate that CALD women (but not CALD men) were more likely to experience gender-based incivility (b = 0.74, SE = 0.37, p = .050) than their non-CALD counterparts. Gender-based incivility was more prominent among CALD councillors (b = 1.68, SE = 0.52, p < .001) than among non-CALD councillors (b = 0.56, SE = 0.18, p < .001). This means that CALD women experience distinctly high levels of gender-based incivility relative to non-CALD women and CALD men during the election campaign. Interaction terms for our sample of elected representatives after the first year in council, however, were not significant, suggesting that CALD councillors might be particularly vulnerable to gender-based incivility during election campaigns. We note the campaign period was also a time for greater gender-based incivility for non-CALD women, suggesting this is a particularly vulnerable time for women seeking election to local government.

In terms of age, young women experienced more gender-based incivility than men at a similar age and compared to older women during the election campaign and into their first year in council (the interaction term was however not significant, see Table 3. Simple slope analysis indicated that age had a negative association with gender-based incivility among women councillors (b = −0.03, SE = 0.01, p < .001), but not among men councillors (p > .05) during the election.

Table 3. Linear regression results predicting incivility with gender and age.

| Incivility | Gender-Based Incivility | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election Period | First Year of Office | Election Period | First Year of Office | |

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| (Intercept) | 3.58*** | 2.69*** | 0.53 | 1.06* |

| Gender | −0.98 | −0.56 | 1.89** | 0.93 |

| Age | −0.04*** | −0.02** | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Location | −0.49** | −0.25 | −0.06 | −0.12 |

| CALD | −0.02 | 0.44* | 0.29 | 0.44 |

| Gender x Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| R-Square | .22** | 0.15** | 0.16** | 0.14** |

| N= | 183 | 181 | 183 | 181 |

*p < .05. **p < .01, ***p<.001; gender: woman = 1, man = 0; location: regional/rural = 1, metro = 0; CALD = 1, non-CALD = 0.

In sum, our results indicate that women overall experience greater gender-based incivility during election campaigns than men and, critically, CALD and younger women are particularly impacted. Most of the incivility came from constituents and alarmingly, from fellow councillors suggesting inadequate training or adherence to professional conduct policies. For an overview of the perpetrators of incivility, see the Appendix.

Although our second survey was conducted only a year into a four-year term, 16% (n = 33) of respondents indicated that they would not run for council in the next elections.7 While this declared attrition rate was comparable among women (17%) and men (16%), a considerably higher number of women (56%) than men (27%) not intending to run in future elections reported experiences of hostility and bullying as one of their top three reasons for not contesting. Given the first survey reveals younger women were disproportionately affected by generalised incivility and gender abuse, we undertook in-depth interviews with this group to identify how incivility might manifest and its potential consequences.

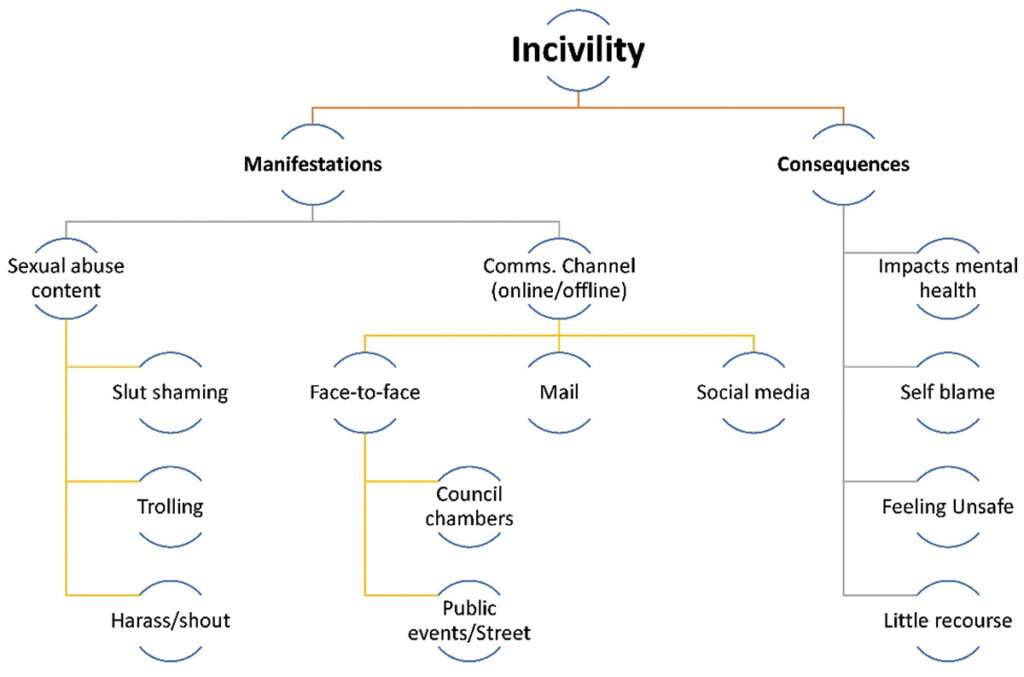

Qualitative findings: interviews with younger women

Consistent with the survey data, the incivility that younger women had encountered came from a range of perpetrators – the media, the public on social media, constituents and other councillors, and it occurred both face-to face and online (see Appendix). For some interviewees, theses encounters had significant personal impacts and led to their decision not to run for council or to recontest. Due to space constraints, we use illustrative quotes to highlight the key manifestations of incivility and its consequences arising from the interviews. These are then summarised in Figure 2.

Manifestations

Respondents’ experienced incivility through different fora, involving both online and offline experiences. In other words, it was multi-modal. Posts on social media were a particularly common form for younger women to receive unpleasant remarks. As one interviewee noted, online incivility often came from: ‘community action groups and things like that, people who utilise social media to either create a diversion or sabotage you, or character assassinate’. (Interview 2, age 34, 1 March 2021). Interviewees also experienced face-to-face hostilities such as during council meetings, and indirectly via written correspondence delivered by hand or post. In one instance, a councillor had received a threatening letter to her home address made from cutting out letters from a magazine to disguise the perpetrator’s identity through hand writing. Perpetrators, ‘send hate mail and threats … that sort of stuff for me as a young mum it was extremely unnerving and very difficult to deal with’. (Interview 2, age 34, 1 March 2021).

Another woman councillor said verbal abuse would come from colleagues in the council chamber, or after a meeting on social media such as her Facebook page. There was little recourse as it was considered part of the norms of the political culture. She stated: “I got yelled at a lot by two councillors, in particular. There was one councillor who constantly interrupted me, yelled at me, told lies about me, in the chamber, on social media, to community members (Interview 1, age 36, 8 March 2021).

The interviewees recalled abuse that specifically spoke to their gender. One interviewee described it as, ‘Slut shaming type stuff. And it always refers to a woman’s sexuality or a woman’s bodily parts or the threats of violence against them in a sexual fashion’, (Interview 2, age 34, 1 March 2021).

Another observed that men did not seem to get the same level of abuse as women:

The level of abuse that [women] copped was just horrific and like really, like sexist crude things sent to them. Constantly. … I just don’t think I have the mental strength or resilience to be able to do it. But I’m frustrated that blokes seem to have it. And they don’t get that level of abuse.

(Interview 5, age 26, 11 March 2021)

Consequences

As a consequence of being subjected to generalised incivility and gender abuse, some councillors said they had experienced low mental wellbeing, and some engaged in self-blame:

For a while for some of the things I got, like hate mail, and not like serious physical threats, but I had like people yelling at me in the street and that kind of thing. And I think maybe if I didn’t have so much else going on in my life that I would have had more resilience to just kind of roll with it maybe?.

(Interview 1, 36, 8 March 2021)

And this reflection:

At the end of the day when you’re elected there’s no one else in your ward that you can rely on or go to for help … it’s just you. So if something goes wrong, then there’s no one else to blame, but yourself. It just adds that like extra level of pressure.

(Interview 5, age 26, 11 March 2021)

Two other findings that came through in the interviews was concern about safety and the inadequate protections against incivility and threats of violence that were deemed a part of politics. Our interviewee’s reference to Brittany Higgins’ rape claim (see introduction for details) illustrated this concern. She said the Higgins allegation,

helped me put my finger on how sort of unsafe and uncomfortable I felt about stepping into such a public domain where there’s basically very little rules on what members of the public can say or do. And not just members of the public, but other councillors and the like. It just doesn’t feel like a safe environment for me to step into. (Interview 7, 33, 5 March 2021)

Similarly, another safety concern arose from the discourse about a high-profile rape allegation against a former federal parliamentarian:

I think we’d have to have less cabinet ministers credibly accused of rape, so I don’t have to live in perpetual fear of my safety … I just can’t see myself ever running for council now”.

(Interview 6, age 45, 5 March 2021)

Women councillors expressed dismay about a lack of oversight and protection from incivility:

I don’t feel as though the political system has the right sort of policies, procedures, mechanisms, like the actual workforce does. In my employment, there would be things that would never be permitted for a client or a co-worker to say or do to me. And to me, the political sphere is just a terribly unsettling domain where there just are not those protections. And so that has to change.

(Interview 7, age 33, 5 March 2021)

And, also this experience:

I was getting some fairly substantial hate mail, and I went to the police, because it was at the point that I thought this needs proper investigation. And the police’s attitude was that I was writing it myself probably for the publicity’.

(Interview 2, age 34, 1 March 2021)

Critically, these experiences weaken women councillors’ intentions of remaining in local government or politics more broadly.

I’m aware of too many female politicians, or candidates who have just been outright harassed for gendered, sexual, racial, whatever anyone can come up with. And it’s kind of terrifying and I’m not willing to put myself in that position. And the added fear when it comes to local government is that people know your local area, they know where you frequent, they know where your kids go to school, they know where you live.

(Interview 7, age 33, 5 March 2021)

Discussion and conclusion

This historic underrepresentation of women in elected politics is a major social problem that requires sustained investment. The Australian case provides a powerful example given the Victorian government’s commitment to gender equality by 2025. This ambitious goal can only be achieved if the mechanisms that push women out of politics are better understood. Here, we focus on one obstacle, incivility – and its connection to gender abuse – which is of increasing salience and plays a critical role in understanding women politicians’ experiences in public life. We bring a mixed methods approach to answer our three research questions.

To our first question about the forms of incivility in local government, we find it is multi-modal, felt both online and in person, and more likely to be gender-based for women, especially younger and CALD women. Our results provide some critical insights to assist in supporting women throughout the election campaign and while serving on the council.

In answer to our second question about whether incivility is a more common experience for men or women, we find incivility is omnipresent across municipalities and cohorts within local government in Victoria. Men and women councillors reported similar levels of generalised incivility, demonstrating the prevalence of this adverse facet of political life. This confirms previous studies that document that incivility is a common experience for politicians (Southern and Harmer 2021) and a barrier influencing their decision to recontest and stay in politics (Majumdar 2021; Parliament of Victoria 2021; Ryall 2017). Our respondents note that this dimension of politics is assumed to be inherent to political culture with very limited recourse measures to mitigate or stop the incivility, and unfortunately more the case if the perpetrator is a constituent as they are not subject to council reprimands. This leads many women to question whether they want to continue in politics given that they are open to significant and severe incivility across multiple platforms – by fellow councillors, their constituents, and the public both directly online and via mainstream media.

Critically, we find that women local politicians are more vulnerable than men to a distinctive form of incivility, which they identify as gender based. What is more, we find that during election campaigns CALD and younger women are most vulnerable to this abuse. It is therefore of no surprise that women consider dropping out of political contestation as they experience compounding forms of incivility. This last point addresses our final research question. A small, but nonetheless meaningful number of women compared to men cite incivility in their top three reasons for not recontesting the next election in 2024.

Previous literature identifies that women councillors and candidates are also carrying heavier domestic burdens that make combining multiple roles – home, life, work and public office – difficult (Carson et al. 2021). Here, we find the added strain of incivility and gender-based abusewith seemingly little protections for councillors’ safety or satisfactory repercussions. As one of our interviewees noted, this was particularly challenging in her role as a new mom and made participation in public life difficult. These compounding challenges provide a clear direction for government agencies and political parties committed to gender parity across government. Policy approaches that focus on mentorship or leadership training must include training on incivility and gender abuse for councillors and council staff. Further, the normative assumption that incivility is a part of politics is incredibly toxic to women, especially those vulnerable to abuse due to their age and CALD status. As many noted in our sample, these behaviours involve workplaces (even though councillors are not legally considered employees) and as such should require adequate safety protections and supports beyond current mechanisms such as poorly enforced Codes of Conduct.

Our results are not without limitation. Our study is focused on Australia as a case study and on local government in one state of the nation. Although we provide an in-depth understanding of these experiences through mixed methods, more work should be done testing our findings for other Australian local governments and beyond. Given consistency of findings within politics and gender literature, we believe our results are generalisable – and that incivility and gender-based incivility are experienced by many local councillors and serve as a barrier to women’s continuation in elected politics. Yet, more work should be done to showcase local governments’ unique position within society and experiences of women in these councils. In this study we capture an election campaign period during a very distinct phase in history, the COVID-19 pandemic. This provides an interesting opportunity to understand the role of incivility in election campaigns that transferred to the digital space and, in doing so, might have intensified experiences of online abuse. More work should be done to understand these experiences during a campaign outside the novel coronavirus pandemic. When councillors can do more in-person events, the form and scale of incivility may manifest differently.

Ultimately, our results reinforce international findings about women politicians’ experiences of multi-modal forms of incivility. We add the first Australian local government study of this kind to the literature and provide critical insight into women’s experiences of being an elected councillor along with the intersecting minority statuses such as gender, CALD status and age that deem women councillors vulnerable to incivility. Given the broad societal aim to achieve a descriptively representative local government, the lessons learned here that certain groups are more vulnerable to incivility (and this may reduce their intentions to recontest) must be addressed if gender parity is to be achieved. Whether it is addressed through better mandatory training of councillors and staff, or new mechanisms for greater oversight of council, media and citizens’ behaviour towards elected representatives, this must be done in ways that engender diverse representation in safe spaces, both online and offline.

Notes

1.

In 2018, the federal government commissioned the National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces, conducted by the Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins. The product of this inquiry was the Respect@Work: Sexual Harassment National Inquiry Report (2020).

2.

3.

The Liberal and national parties that form the Coalition do not support gender quotas, instead it promotes voluntary targets.

4.

Mentees in the program were selected by demonstrating ‘a commitment to political participation’.

5.

For respondents who said they would not recontest the election, a further question was asked with the wording: ‘I will not run for council again because … ’ Respondents were given 7 choices plus an open text option to provide their reason why and asked to rank order their top 3 choices if multiple reasons applied. The options were: 1) It takes up too much time away from family and home responsibilities; 2) It takes up too much time away from career; 3) It pays too little relative to the time demands; 4) I experienced hostility and/or bullying on social media; 5) I experienced hostility and/or bullying in person; 6) I experienced gender abuse (either online or in person); 7) It is too difficult to make the changes that I want to make, 8) It is not the experience I thought it was going to be (please explain why in the text box).

6.

The interview schedule and metadata of participants is available on request.

7.

By comparison 17% indicated they would run, 58% said it was too early for them to say, while nine per cent did not provide an answer to this question.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to sincerely thank Mr Liam Fallon for his research assistance facilitating the research interviews. We also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments that were of great assistance to us. This research has ethics approval for research with human subjects by the University of Melbourne: Ethics ID Number: 2057751.1

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

This research is part of an Australian Research Council Linkage Project, LP190101189, in partnership with the Victorian Local Governance Association entitled ‘Women in Local Government: Understanding their Political Trajectories’.

References

5050 Vision. 2019. Why is Gender Equity Important in Local Government, 5050 Vision. <https://www.5050vision.com.au/documents/40253852/Why%20is%20Gender%20Equity%20Important.pdf>.

Akhtar, S., and C. M. Morrison. 2019. “The Prevalence and Impact of Online Trolling of UK Members of Parliament.” Computers in Human Behavior 99:322–327. Crossref. ISI.

Andersson, L., and C. Pearson. 1999. “Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace.” The Academy of Management Review 24 (3): 452–471. Crossref. ISI.

Banks, J. 2021. Power Play: Breaking Through Bias, Barriers and Boys’ Clubs. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Books.

Barnes, T. D., and E. Beaulieu. 2019. “Women Politicians, Institutions, and Perceptions of Corruption.” Comparative Political Studies 52 (1): 134–167. Crossref. ISI.

Bossio, D., and A. E. Holton. 2018. “The Identity Dilemma: Identity Drivers and Social Media Fatigue Among Journalists.” Popular Communication 16 (4): 248–262. Crossref. ISI.

Briggs, J. 2000. “‘What’s in It for women?” the Motivations, Expectations and Experiences of Female Local Councillors in Montreal, Canada and Hull, England.” Local Government Studies 26 (4): 7. Crossref. ISI.

Campbell, R., and J. Lovenduski. 2016. Footsteps in The Sand: Five Years of the Fabian Women’s Network Mentoring and Political Education Programme, Fabien Women, <https://www.fabians.org.uk/wp-/uploads/2016/01/FootstepsInTheSand_lo.pdf>.

Carson, A, Mikolajczak, G, Ruppanner, L. 2021. The missing cohort: Women in local government Australiasian Parliamentary Review 36 2 70–90 https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.20220131061199 ISI.

Celis, K., S. Childs, J. Kantola, and M. L. Krook. 2014. “Constituting Women’s Interests Through Representative Claims.” Politics & Gender 10 (2): 149–174. Crossref. ISI.

Ceron, A. 2017. Social Media and Political Accountability: Bridging the Gap Between Citizens and Politicians. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Crossref.

Cortina, L. M. 2008. “Unseen Injustice: Incivility as Modern Discrimination in Organizations.” Academy of Management Review 33 (1): 55–75. Crossref. ISI.

Cortina, L. M., D. Kabat-Farr, E. A. Leskinen, M. Huerta, and V. J. Magley. 2013. “Selective Incivility as Modern Discrimination in Organizations: Evidence and Impact.” Journal of Management 39 (6): 1579–1605. Crossref. ISI.

Cortina, L. M., V. J. Magley, J. H. Williams, and R. D. Langhout. 2001. “Incivility in the Workplace: Incidence and Impact.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6 (1): 64–80. Crossref. PubMed.

Crowder-Meyer, M., and B. Lauderdale. 2014. “A Partisan Gap in the Supply of Female Potential Candidates in the United States.” Research & Politics 1 (1): 205316801453723. Crossref.

Di Meco, L. 2019. Women, Politics & Power in the New Media World, Report, #ShePersisted<https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5dba105f102367021c44b63f/t/5dc431aac6bd4e7913c45f7d/1573138953986/191106+SHEPERSISTED_Final.pdf>.

Duncan, E., and J. Baird. 2021. “Leaked Liberal Report Shows Concerns About Women and Culture in the Party Were Raised as Early as 2015”. ABC News 8 April URL https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-04-08/leaked-liberal-party-report-shows-ongoing-concerns/13292160.

Fichman, P., and M. W. McClelland. 2020. “The Impact of Gender and Political Affiliation on Trolling”. First Monday URL https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/11061. Crossref.

Ghazarian, Z., and Lee-Koo K., eds. 2021. Gender Politics: Navigating Political Leadership in Australia. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

Gorrell, G., M. E. Bakir, I. Roberts, M. A. Greenwood, and K. Bontcheva. 2020. “Which Politicians Receive Abuse? Four Factors Illuminated in the UK General Election 2019.” EPJ Data Science 9 (1): 18. Crossref. ISI.

Herrick, R., and S. Thomas. 2023. “Research Note: Rise in Violence Against U.S. Mayors: 2017 to 2021.” Social Science Quarterly N/A (N/a) 104 (2): 81–91. Accessed April 3, 2023. Crossref. ISI.

Herrick, R., S. Thomas, L. Franklin, M. Godwin, E. Gnabasik, and J. R. Schroedel. 2021. “Physical Violence and Psychological Abuse Against Female and Male Mayors in the United States.” Politics, Groups & Identities 9 (4): 681–698. Crossref.

Hills, J. 1983. “Life-Style Constraints on Formal Political Participation—Why so Few Women Local Councillors in Britain?” Electoral Studies 2 (1): 39–52. Crossref. ISI.

Holman, M. 2017. “Women in Local Government: What We Know and Where We Go from Here.” State & Local Government Review 49 (4): 285–296. Crossref.

IPU [Inter-Parliamentary Union]. 2018. Sexism, Harassment and Violence Against Women in Parliaments in Europe. URL: Issues Brief, Inter-Parliamentary Union. https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/issue-briefs/2018-10/sexism-harassment-and-violence-against-women-in-parliaments-in-europe.

IPU [Inter-Parliamentary Union]. 2022. “Monthly Ranking of Women in National Parliaments.” IPU Parline: Global Data on National Parliaments. URL. https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=6&year=2022.

Jakimow, T. 2022. “Roadblocks to Diversity in Local Government in New South Wales, Australia: Changing Narratives and Confronting Absences in Diversity Strategies.” Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance 26:74–93. Crossref.

Johnson, C. 2015. “Playing the Gender Card: The Uses and Abuses of Gender in Australian Politics.” Politics & Gender 11 (2): 291–319. Crossref. ISI.

Kreis, R. 2017. “‘The ‘Tweet Politics’ of President Trump.” Journal of Language and Politics 16 (4): 607–618. Crossref. ISI.

Lumsden, K., and H. Morgan. 2017. “Media Framing of Trolling and Online Abuse: Silencing Strategies, Symbolic Violence, and Victim Blaming.” Feminist Media Studies 17 (6): 926–940. Crossref. ISI.

Majumdar, M. 2021. “The Missing Women of Australian Politics: How Violence Against Women Creates Barriers to Female Representation.” Julia Gillard Next Generation Internship Report 2020-2021 Emily’s List, URL. <https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/emilyslistaus/pages/463/attachments/original/1628741737/EmilysList_JGNG_report2021_v4.pdf?1628741737>.

March4Justice. n.d. Hear Me. See Me. Act!. https://www.march4justice.org.au/.

Martin, F. 2018. “Tackling Gendered Violence Online: Evaluating Digital Safety Strategies for Women Journalists.” Australian Journalism Review 40 (2): 73–89.

Morrissey, B., and S. Yell. 2018. “Performative Trolling: Szubanski, Gillard, Dawson and the Nature of the Utterance.” Persona Studies 2 (1): 27–40.

O’Sullivan, P. B., and C. T. Carr. 2018. “Masspersonal Communication: A Model Bridging the Mass-Interpersonal Divide.” New Media & Society 20 (3): 1161–1180. Crossref. ISI.

Parliament of Victoria. 2021. Inquiry into the Impact of Social Media on Victorian Elections and Victoria’s Electoral Administration. Electoral Matters Committee. URL: https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/images/stories/committees/emc/Social_Media_Inquiry/EMC_Final_Report.pdf.

Parmelee, J. H., and S. L. Bichard. 2011. Politics and the Twitter Revolution: How Tweets Influence the Relationship Between Political Leaders and the Public. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Pérez-Escolar, M., and J. M. Noguera-Vivo. 2022. Hate Speech and Polarization in Participatory Society. New York: Routledge.

Rheault, L., E. Rayment, and A. Musulan. 2019. “Politicians in the Line of Fire: Incivility and the Treatment of Women on Social Media.” Research & Politics 6 (1): 1. Crossref. ISI.

Ryall, G. 2017. ““Online Trolling Putting Women off Politics, Says Union”. BBC 20 May URL https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-39940086.

Ryan, C., B. Pini, and K. Brown. 2005. “Beyond Stereotypes: An Exploratory Profile of Australian Women Mayors.” Local Government Studies 31 (4): 433–448. Crossref. ISI.

Sawer, M. 2002. “The Representation of Women in Australia: Meaning and Make-Believe.” Parliamentary Affairs 55 (1): 5–18. Crossref. ISI.

Schilpzand, P., I. E. De Pater, and A. Erez. 2016. “Workplace Incivility: A Review of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 37:S57–S88. Crossref. ISI.

Schreiber, R. 2016. “Gender Roles, Motherhood, and Politics: Conservative Women’s Organizations Frame Sarah Palin and Michele Bachmann.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 37 (1): 1–23. Crossref. ISI.

Southern, R., and E. Harmer. 2021. “Twitter, Incivility and ‘Everyday’ Gendered Othering: An Analysis of Tweets Sent to UK Members of Parliament.” Social Science Computer Review 39 (2): 259–275. URL. Crossref. ISI.

Sullivan, K. V. R. 2021. “The Gendered Digital Turn: Canadian Mayors on Social Media.” Information Polity 26 (2): 157–171. Crossref. ISI.

VAGO [Victorian Auditor-General’s Office]. 2020. Sexual Harassment in Local Government. VAGO, 9 December. https://www.audit.vic.gov.au/report/sexual-harassment-local-government?section.

Victorian State Government. 2016. Safe and strong: A Victorian Gender Equality Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.vic.gov.au/safe-and-strong-victorian-gender-equality.

Vîrtosu, I. I. 2022. “How COVID-19 Changed “The Anatomy” of Political Campaigning.” Central and Eastern European eDem and eGov Days 341 (March): 351–369. Crossref.

Wagner, A. 2020. “Tolerating the Trolls? Gendered Perceptions of Online Harassment of Politicians in Canada.” Feminist Media Studies 22 (1): 32–47. Crossref. ISI.

Walsh, K.-A. 2013. The Stalking of Julia Gillard. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Walsh, M. 2021. “She Just Won’t Lie Down and Die: Gillard, Misogyny and Australian Political Leadership.” In Gender Politics: Navigating Political Leadership in Australia, edited by Z. Ghazarian and Lee-Koo K. 47–55. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

Weber, M., and M. Davis. 2020. “Feminism in the Troll Space: Clementine Ford’s Fight Like a Girl, Social Media, and the Networked Book.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (7): 944–965. Crossref.

Weeks, A. C., and L. Baldez. 2015. “Quotas and Qualifications: The Impact of Gender Quota Laws on the Qualifications of Legislators in the Italian Parliament.” European Political Science Review 7 (1): 119–144. Crossref. ISI.

Williams, B. 2020. “It’s a Man’s World at the Top: Gendered Media Representations of Julia Gillard and Helen Clark.” Feminist Media Studies 1–20. Crossref. ISI.

Wolbrecht, C., and D. E. Campbell. 2007. “Leading by Example: Female Members of Parliament as Political Role Models.” American Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 921–939. Crossref. ISI.

Wright, K. A. M., and J. Holland. 2014. “Leadership and the Media: Gendered Framings of Julia Gillard’s “Sexism and misogyny” Speech.” Australian Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 455–468. viewed 28 January 2022. <http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10361146.2014.929089>. Crossref. ISI.

Appendix

Perpetrators of Incivility

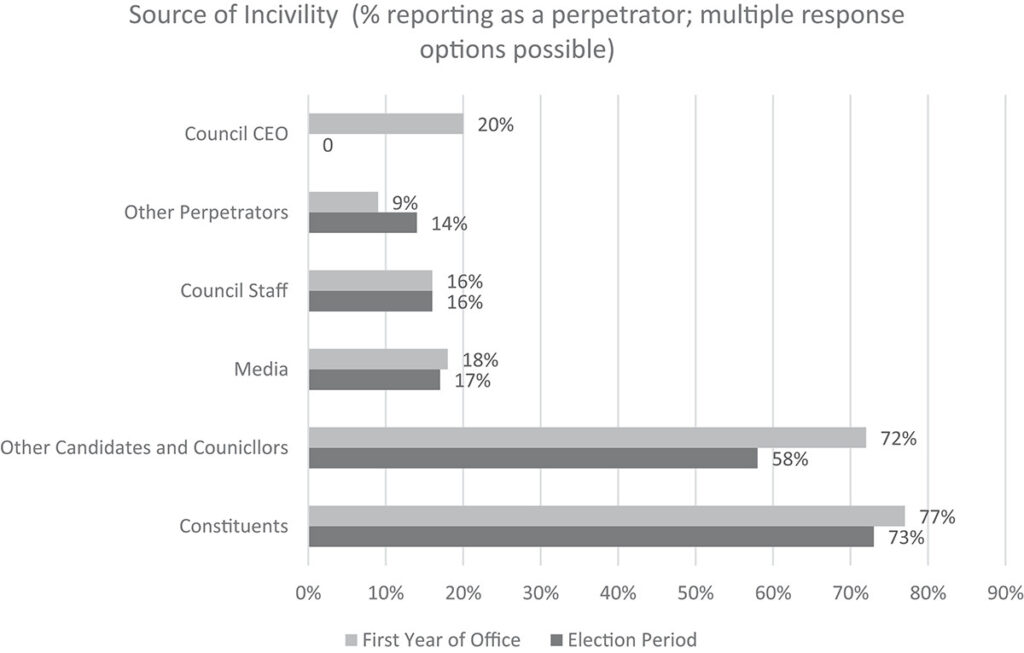

Figure 2 provides the descriptive overview of those identified as perpetrators of incivility. Among those who have experienced at least one uncivil behaviour in the election campaign, the majority pointed either to constituents (73%) or other candidates and councillors (58%) as central to their negative experiences (note that respondents could choose more than one option). The media (17%), council staff (16%) and other perpetrators (14%) were all less commonly reported but also featured as perpetrators.

Among those who have experienced some incivility while elected to council, the majority pointed either to constituents (77%) or other councillors (72%) as central to their negative experiences (again, respondents could choose more than one option).

Council CEO (20%), the media (18%), council staff (16%) and other perpetrators (9%) were all mentioned less commonly. We did not find any significant gender differences in the perpetrators of incivility, noting that our question referred to all forms of incivility, not just gender-based ones. (See Figure 3)